Welcome to the first Friday of September and the eleventh (!) week of the Summer Library Series here at What She Might Think, where all summer writers have visited and reflected on their childhood experiences at the library.

This week's library author is poet kathryn l. pringle, who grew up digging through the shelves and the past, at the Van Nuys Public Library in Van Nuys, California.

*

|

| kathryn l. pringle and her father |

ON RAISING AN ONTOLOGICAL ARCHITECT

by kathryn l. pringle

I needed cold, hard FACTS and I knew exactly where to get them: the Van Nuys Public Library.

|

Van Nuys Branch of the Los Angeles Public Library,

|

When I asked my father, now 86 years old, what he could remember about me and the public library in Van Nuys, he thought for a moment and said, “When you were really, really little you loved The Little Engine that Could.”

My father would take my sister and me to the library often. I want to say he was an avid reader, but compared to my mother, who always had a book in her hands unless she was working or eating, he was just a little above average on this scale. We were, in fact, a family of readers and so economics came into play. A family on a budget equaled a family that frequented the public library. That, and I feel certain that my father didn’t want a house with books on every wall (which, ultimately we did have, because everyone knows once you love a book it must always be within reach).

|

Fernando - Photograph by Vahe Manoukian  , ,

used with photographer's permission

|

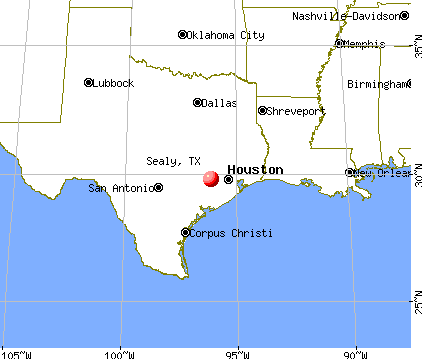

There was no such thing as a quick trip to the library (I maintain this is still true today). We had to park a little bit out of the way because the library was in this giant quad, filled with government buildings and replete with well-maintained plants, grassy areas, and my second-favorite statue (the first being the Amelia Earhart statue, of course): Fernando.

I both loved and feared Fernando. He stood so strong and fierce and half naked. He was maybe my second crush (after Amelia Earhart). So with the walk from the car, my lingering with Fernando, and my father’s usual answers about the courthouse (I’ll get to that in a minute), it took about twenty minutes for us to actually get INTO the library itself.

The library was our activity center. We didn’t do scouts or play sports or take music or dance lessons - we went to the library.

Once inside, the touching of every book in the children’s section was an absolute must. How, with those soft plastic dust covers and that library book smell - the smell that to this day I swear is the smell of potential energy - could anything else have come first?

|

| kathryn l. pringle |

Then, my use of the library had been dictated by whim. Picture books and puzzle books were IT. But one day, quite suddenly, everything changed. The Van Nuys Public Library and its place as the most important institution on Earth revealed itself to me when, at the ripe old age of eight years old, I decided to become an archaeologist. Being the diligent, overachieving student that I was, I therefore had to begin my studies immediately. My subscription to

Archaeology magazine, with its large print and too-easy maze games leading through ancient tombs, had been disappointing. I was serious and needed serious books. I needed cold, hard FACTS and I knew exactly where to get them: the Van Nuys Public Library.

At eight years old I had finally realized that the library was this amazing RESOURCE. It was this place that was filled with critical information and it was all mine for the taking. And I took the hell out of it. (Incidentally, it was about this age that I also realized the Van Nuys Public Library sat in the same quad and directly across from Van Nuys County Courthouse and Los Angeles Superior Court--as well as Van Nuys City Hall, the Los Angeles Sheriff Department, and the Los Angeles County Registrar--and I began suspecting that all people in the vicinity NOT entering the library were criminals. . . thus, the many questions for my father to field on the way into the library.)

|

Photograph by Vahe Manoukian  , used with photographer's permission , used with photographer's permission

|

I began with books on Ancient Egypt and branched out in every possible direction. Sure, there was the occasional books by Dumas, Twain, Blume, Poe. . . but mostly there was ancient history and bones. By junior high I was still obsessed. I was so dedicated to pursuing archaeology that my nickname was “Digger.” I even carved a replica of an ancient Egyptian barge out of balsa wood, and it was so cool the school librarian asked if she could put it on display in the school library.

Ultimately, however, I didn’t become an archaeologist. I branched off into a related field, a field that I had always been leaning toward but hadn’t realized. I became a writer--a cultural anthropologist or an ontological architect of sorts. And it all still begins with a visit to the public library. Every book I write starts there with massive amounts of research. Not much has changed since I was eight.

*

kathryn l. pringle is a poet living in Oakland, Ca. Her book fault tree recently

won Omindawn’s 1st/2nd book prize (selected by CD Wright). She is also the author of Right New Biology (Heretical Texts/Factory School), The Stills (Duration Press), and Temper and Felicity are lovers (TAXT).

Her poems can be found in journals such as the Denver Quarterly, Fence, Phoebe

, and horse less review. Her work can also be found in the anthologies Conversations at the Wartime Cafe: A Decade of War (

WODV Press)

, I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

(Les Figues), and forthcoming in The Sonnets: Rewriting Shakespeare

(Nightboat Books).

Check out worldcat.org to find out whether your library has books by kathryn l. pringle.