|

photo by Alan Levine,

used under creative commons license

|

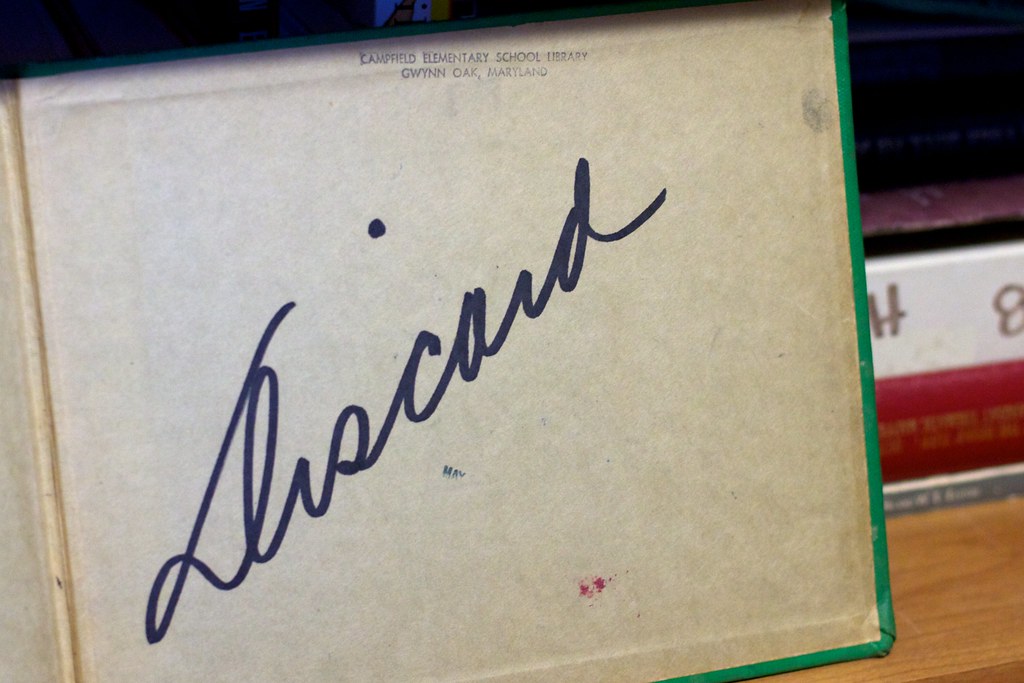

Today's installment of the Summer Library Series focuses on this, the discarded library book. Writer TJ Beitelman's mother bought one such book for him as a boy, and it was because of its library markings that he took such good care of it. . . not knowing it wouldn't be going back.

*

by TJ Beitelman

. . . at the time, the fact that my mother produced

an honest-to-God library book [. . .] convinced me,

once and for all, that she was not bound

by any ordinary rules of the social contract.

Sully Elementary School library in Sterling, VA

where his mother likely bought the discarded

Down Singing River

|

My mom was magic in some (not all) of the ways above. But mostly she was magic in other, more unconventional ways: she crashed Harleys, for instance. Also she let me watch her put on her make-up every morning—which both fascinated and bewildered me—and she made good on her promise never to wear red nail polish because, well, it sort of freaked me out. She also took me to weird shit, like ballet and dinner theater and also to some semi-respectable, suburban religious cult-like thing involving rainbows and the randomly Spanish moniker “De Colores.” Almost all of this was a mystery to me. Still is. Thus: for me, mysteries became (or never stopped being) sacred.

Case in point:

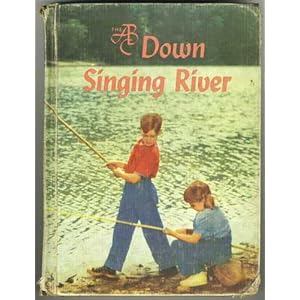

Case in point:One of the sustaining original mysteries of my life is a library book called Down Singing River. Somehow, long about third grade, my mother presented it to me as mine to keep forevermore.

The book itself was magic too. It had stories in it. One about a talking fish. Another about an old fish—there was, to be sure, a decidedly ichthyological bent to the book—who got plucked up from his river habitat by a hungry bird. I seem to recall the fish wiggled his way out of his predicament, but I was always a little nervous and unsure about how my mother wiggled into possessing this book that seemed for all the world to be the property of the citizens of the town on the suburban outskirts where we lived our not-so-normal life.

Now I understand that libraries sometimes sell off portions of their collection to raise funds and make room for new books, but at the time, the fact that my mother produced an honest-to-God library book—with the circulation card in it and everything—convinced me, once and for all, that she was not bound by any ordinary rules of the social contract.

My mom isn’t with us anymore—not in flesh and blood, anyway. But I still have Down Singing River. And I still have the particular notion of what is sacred that my mother (and this book) helped instill in me.

I wrote a novel about sacred texts. It comes out next summer. In it, I excerpted passages from Down Singing River. The part about the talking fish and the other old fish that gets plucked up. What is sacred, to me, about that text is that it originally belonged to someone else. Lots of someone elses. That’s what libraries do: they house the words, the wisdom, the physical forms of a shared body of cultural knowledge.

|

| "Boy, Reading"

Used with photographer's permission |

I could press my luck and make a metaphor about rebirth and resurrection. But I won’t. All I’ll say in closing is that the books we keep and the books we share will always and forever bind us together. There are more human things, probably: kissing someone on the mouth, the neck. Braiding someone’s hair. Holding hands. Feeding those we love. But for mystery, magic, for sharing a notion of that which is enduring and sacred, we probably can’t do much better than books.

*

|

| TJ Beitelman |

TJ Beitelman lives, teaches, and writes in Alabama and is the author of the chapbooks Pilgrims: A Love Story (Black Lawrence Press) and Thirteen Curses (and Other Love Poems) (Dream Horse Press). His book of poems, In Order to Form a More Perfect Union, is forthcoming from Black Lawrence Press this summer and his novel, John the Revelator, also from Black Lawrence Press, will be released next summer.

Please join What She Might Think next Friday for John Kenny's

piece "My Regrettable Non-Relationship with Libraries,"

in which he details his childhood seduction by comic books.

in which he details his childhood seduction by comic books.