Welcome to this week's installment of the Summer Library Series in which professional authors reflect on their childhood experience with their local library. Today's author is Jack Kaulfus, who hails from Texas and had a library card at the Seguin-Guadalupe County Library.

*

A KIND OF BEACON

I fell in love with The Library Man over the summer between my sophomore and junior year in high school. He was tall and lean and sensitive, and he had some longish hair and a choker under his button- down shirt. He was a new librarian, probably in his early 20s, and he was married. He wasn’t from my small town.

I was always doing this in high school – becoming infatuated with older, disinterested feminine men who might want to talk to me about books or music. It was good practice for later, when I’d become more appropriately obsessed with older, disinterested butch women who might want to talk to me about books or music.

I had only the vaguest idea about what I wanted from the The Library Man. My friends believed I was in love with him, and I didn’t discourage them. It was much safer to cop to an impossible crush than to come out as queer. It didn’t seem a simple case of puppy love to me, however. I knew he was married. I knew I didn’t want to sleep with him. But I also knew I wanted to be in the library with him every Monday, Thursday, and Friday afternoon when he was working.

The year before had been particularly frustrating, and in the spring I’d decided to quit basketball (after many long years of promising athletic training and early promotion to the varsity team) to join the school paper instead. I had also clawed my way into some honors and AP classes for the next year, but it took work to convince the counselor that I could handle being in classes with kids who didn’t throw chairs. I wasn’t sure if I was going to succeed, as I’d been consistently dumb-tracked since third grade when I got myself kicked off the gifted and talented program’s shortbus, but I knew I needed to try.

Guadalupe County Library in the early ‘90s was not a hot destination for young folks, but it smelled good inside, and the air conditioning was icy. I’d bike there in the heat of the afternoon to sit at a table and gaze at The Library Man over stacks of books I wanted to understand but couldn’t.

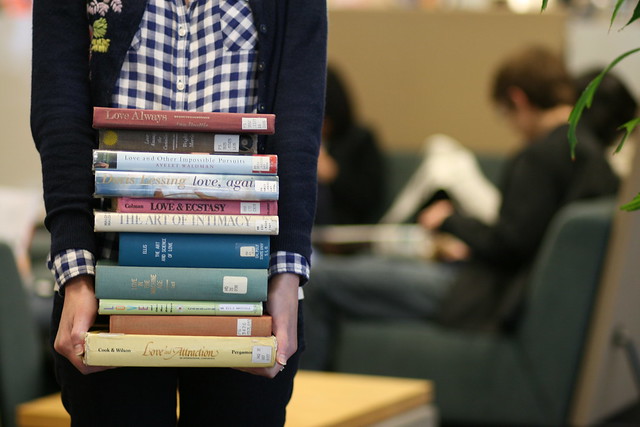

Our relationship was all business. We rarely exchanged more than a few sentences over the counter as I checked out books. He might ask: “Writing a paper?” Or say: “Gotta love Hegel.” To which I’d respond in a weak affirmative. The truth was, I had no idea what I was doing, but I didn’t know how to tell him that. I’d burned through the books in the children’s and young adult section at least twice, and I felt ready for the next big thing. In one stack, I might have Hume, Plato, Feynman, and Hawking. Three days later, I might want to take Browning, Carlyle, Euclid, and Kafka home. At night I’d struggle through a few pages of each dusty tome and then give up.

I know now that I wanted him to help me shed my years of depressing small-town athletic obsession and usher me into a world governed by reason and elegant sentence structure rather than point-spread. At the time, however, I’d watch his lovely dark hair and slender hands as he labeled shelf-talkers and joked with his cohorts behind the check-out counter. I’d puzzle over whether I wanted to kiss him or buy him a coffee somewhere the cups didn’t have a HOT BEVERAGE warning label.

I drifted in a sea of possibility all summer, hoping I’d come to light on a shelf with something that made sense. The books themselves could be deceitful. The only book on homosexuality in the place was a parenting book for unfortunate dads in the fifties who happened to have effeminate sons. There were cartoons depicting ways to shame your fairy boy into hating himself and lists of “tough love” redirection techniques. There were two books on modern art, and neither of them offered color plates. A book on Apartheid was consistently mishelved in “African American History.”

I don’t know if The Library Man was really all that. He had, after all, taken a job in a town long dead from sheer lack of curiosity. If I’d been able to formulate the question I needed him to answer, he might have laughed at me or led me to a shelf of Encyclopedias or something. He was a kind of beacon, though, that reassured me of the possibility of connections I could only dream of understanding. Just his presence was a comfort. I wish I could thank him now, but I don’t even remember his name.

Jack Kaulfus lives, writes, and teaches in Austin, Texas. Their story "Troglodytes" was selected as one of the top 100 stories published in 2006 (StorySouth). Their most recent story, "The End of Objects," was honored by A Cappella Zoo with the Apo Specimen award. They are currently shopping around a book of stories entitled, The Answer Is Please.

*

by Jack Kaulfus

Guadalupe County Library in the early ‘90s

was not a hot destination for young folks,

but it smelled good inside, and the air

conditioning was icy.

I fell in love with The Library Man over the summer between my sophomore and junior year in high school. He was tall and lean and sensitive, and he had some longish hair and a choker under his button- down shirt. He was a new librarian, probably in his early 20s, and he was married. He wasn’t from my small town.

|

| Seguin-Guadalupe County Public Library |

Guadalupe County Library in the early ‘90s was not a hot destination for young folks, but it smelled good inside, and the air conditioning was icy. I’d bike there in the heat of the afternoon to sit at a table and gaze at The Library Man over stacks of books I wanted to understand but couldn’t.

|

|

Used with photographer's permission

|

I drifted in a sea of possibility all summer, hoping I’d come to light on a shelf with something that made sense. The books themselves could be deceitful. The only book on homosexuality in the place was a parenting book for unfortunate dads in the fifties who happened to have effeminate sons. There were cartoons depicting ways to shame your fairy boy into hating himself and lists of “tough love” redirection techniques. There were two books on modern art, and neither of them offered color plates. A book on Apartheid was consistently mishelved in “African American History.”

I don’t know if The Library Man was really all that. He had, after all, taken a job in a town long dead from sheer lack of curiosity. If I’d been able to formulate the question I needed him to answer, he might have laughed at me or led me to a shelf of Encyclopedias or something. He was a kind of beacon, though, that reassured me of the possibility of connections I could only dream of understanding. Just his presence was a comfort. I wish I could thank him now, but I don’t even remember his name.

*

Please return next Friday for Dan Powell's reflections on

the mobile library in Colwich in Staffordshire, England.